Somewhat related: Don’t scandalize away kids’ idealism: Clueful questions for me from history class at George Washington. – D.R.

Somewhat related: Don’t scandalize away kids’ idealism: Clueful questions for me from history class at George Washington. – D.R.

My pushy reporter in The Solomon Scandals novel, Jonathan Stone, wanted me to delete a more formal Rothman bio (“too short, too press releasy”).

To help busy readers, I’ll stubbornly stick with the abbreviated version. But here’s a partial prequel to the Stone-Rothman Q&A, where Stone grilled me about my investigation of the government office leasing program. I’ll also include some during and after.

STONE: The Solomon Scandals is a newspaper and political novel that depicts D.C. as a white-collar factory town in the late 20th century. Exactly where did your family stand in the social hierarchy? We’ll do the Education of Henry Adams routine—personal history mixed in with national and local history—and add some journalistic odds and ends for good measure. Don’t let this get to your head, Rothman. I’d never be messing with a second Q & A if a sadistic history professor at George Washington University hadn’t assigned Scandals as required reading.

ROTHMAN: Well, I remember what good friends my sister and I were with Caroline and JFK Jr. Mere parvenus, though. The Rothmans’ own D.C. ties go back to the dawn of the Republic, or at least back to when people got serious about draining the swamps.

More accurately, my great-grandfather was a Jewish tax collector under the Czar, my grandfather was a painter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and my father reverted back to being a bureaucrat. I grew up in Fairfax County, Virginia, on the very outer fringes of the Washington elite, the same social stratum where I’d place you.

More accurately, my great-grandfather was a Jewish tax collector under the Czar, my grandfather was a painter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and my father reverted back to being a bureaucrat. I grew up in Fairfax County, Virginia, on the very outer fringes of the Washington elite, the same social stratum where I’d place you.

Our neighbors didn’t set policy at a cosmic level, but some worked for and befriended those who did. A mile or so from us, I can recall running into Robert McNamara, secretary of defense during the Vietnam War, while he presided over a party from an armchair. It might as well have been a throne. My friends and I were simply passing through to another part of the house, so this was only a glimpse, but you could see the D.C. hierarchy in people’s body language.

Wait. Did I actually stop and tell McNamara what I thought of the Vietnam War? Oh, to think so, but after four decades memories can fuzz up, and I doubt I did. I just wish McNamara had been still more formidable. Maybe he could have more successfully passed on his private ambivalence about Vietnam to Lyndon Johnson.

STONE: Yep, “outer fringes of the elite,” all right—that’s hardly a soul-to-soul talk with McNamara. But you did know a Washington Post editor, a fixture on L Street.

ROTHMAN: E.J., your boss in Scandals, is inspired in part by a kindly and neighborly man with a salt-and-pepper flattop. B. F. Henry worshipped J. Russell Wiggins, the predecessor of Ben Bradlee, the Watergate editor. You can read B.F.’s obit here.

STONE: What about the Watergater mentioned briefly in Chapter 11 of Scandals? Did he exist?

ROTHMAN: Harry Dent, Sr., a future Watergate defendant, lived on the block behind us. While working for Sen. Strom Thurmond, he helped devise the Southern Strategy which helped put Richard Nixon in the White House in the first place. As reported by the New York Time, he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor because he didn’t think he could get a fair trial. My parents simply knew the Dents as good neighbors. I’ve fictionalized the quick mention in Chapter 11.

ROTHMAN: Harry Dent, Sr., a future Watergate defendant, lived on the block behind us. While working for Sen. Strom Thurmond, he helped devise the Southern Strategy which helped put Richard Nixon in the White House in the first place. As reported by the New York Time, he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor because he didn’t think he could get a fair trial. My parents simply knew the Dents as good neighbors. I’ve fictionalized the quick mention in Chapter 11.

Mostly, our neighborhood south of Alexandria was a mix of upcoming executives, white-collar-factory foremen, and below—far better for a future reporter and novelist than a purely elite community. “Factory town” applies since nearly everyone worked for the federal government or served people who did. Back in those days, as I recall, the Washington Post ran its civil service column on the front of the local section. Or was it the comic page? Either place, The Federal Diary would have fit.

My parents were hardly in the thick of the McNamara crowd. As a small-time bureaucrat, my father spent decades examining Indian land claims, so maybe my interest in past scandals is a little hereditary. Seymour Solomon is pathetic at real estate-related crimes compared to the feds of yore, given all the broken treaties. You might say my father was cleaning up after the misdoings of certain national politicians and their provincial friends and other hangers-on, or “operators” in fatherspeak. But I can’t say much about his work, because, like many factory hands, he rarely discussed it at home. I visited his office just once, when I was very young; and even then he may not have introduced me to his colleagues. Remember the drunken Lucky O’Brien, your source in Scandals? Let’s just say that some of my father’s co-workers were at that level, complete with gambling debts and anti-Semitism.

On my mother’s side, my family had ties with the elite in Natchitoches, Louisiana, the Steel Magnolias town, going back to the 1860s. I can remember the mayor giving us a personal tour of Natchitoches from an open convertible; might political donations from my grand-uncle have prompted this hospitality, as a collateral benefit? I don’t know. The whole experience was good training for writing about Power People, satirically or otherwise. Never mind the D.C. mystique; with a little more hubris thrown in, weren’t JFK and LBJ just cousins of the mayor of Natchitoches? That’s my late grand-uncle’s store you see above to the left, “the oldest general store” in Louisiana if you go by Wikipedia. Uncle Sidney knew some members of the Long family, and if nothing else, I’m grateful to Huey for inspiring All the King’s Men, even if it happened a little unwittingly. ATKM’s mention in Scandals is not an accident.

On my mother’s side, my family had ties with the elite in Natchitoches, Louisiana, the Steel Magnolias town, going back to the 1860s. I can remember the mayor giving us a personal tour of Natchitoches from an open convertible; might political donations from my grand-uncle have prompted this hospitality, as a collateral benefit? I don’t know. The whole experience was good training for writing about Power People, satirically or otherwise. Never mind the D.C. mystique; with a little more hubris thrown in, weren’t JFK and LBJ just cousins of the mayor of Natchitoches? That’s my late grand-uncle’s store you see above to the left, “the oldest general store” in Louisiana if you go by Wikipedia. Uncle Sidney knew some members of the Long family, and if nothing else, I’m grateful to Huey for inspiring All the King’s Men, even if it happened a little unwittingly. ATKM’s mention in Scandals is not an accident.

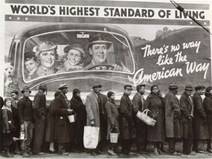

In general zeitgeist, our small-townish neighborhood in Northern Virginia was a long way from a Deep Southern city like Natchitoches; we’re talking about few stray dogwoods, not a place fragrant with magnolias. The most salient trait when I was growing up, beyond the friendliness of the Dutch Supper variety, was our own local brand of Eisenhower- and Kennedy-era optimism, just the reverse of the darkness in The Education of Henry Adams. We were a miniature East Coast California, full of modern people who had reinvented themselves, except that once they settled on their new identities, they were more likely to stick to them. The government, civilian or military, was all. McLean, where you grew up, was in many respects the same, although more members of the true elite lived there, Kennedys included. The genuine D.C.-area elite in many cases summered in New England and sent their children to private schools, as opposed to enduring weekends at Rehoboth Beach and trusting the public schools. Of course, by old Adams standards, even some prominent Georgetown names were mere gatecrashers.

Beaten down in New York by the Great Depression, my father himself had arrived in the D.C. area before World War II after losing his accounting-related job to a relative of the boss; and during most of my childhood he was incapable of imagining me not working for government. We might as well have been in some ways a neighborhood of assembly-line laborers and foremen in Detroit thinking that the UAW-level wages would forever last, except that in D.C. the good luck did not die off, and even now the Great Recession is less evident than elsewhere. Racially, too, the Wellington-Tauxemont neighborhood south of Alexandria was homogenous: no African-Americans lived there during my childhood as far as I recall, and perhaps no Asians or Latinos did, either. And of course the Post and Star were the only papers that most people in the neighborhood read, with the possible exceptions of the Alexandria Gazette and the Northern Virginia Sun and New York Times. No Internet, alas, no National Public Radio, and just three television networks to tell us the way it was.

Beaten down in New York by the Great Depression, my father himself had arrived in the D.C. area before World War II after losing his accounting-related job to a relative of the boss; and during most of my childhood he was incapable of imagining me not working for government. We might as well have been in some ways a neighborhood of assembly-line laborers and foremen in Detroit thinking that the UAW-level wages would forever last, except that in D.C. the good luck did not die off, and even now the Great Recession is less evident than elsewhere. Racially, too, the Wellington-Tauxemont neighborhood south of Alexandria was homogenous: no African-Americans lived there during my childhood as far as I recall, and perhaps no Asians or Latinos did, either. And of course the Post and Star were the only papers that most people in the neighborhood read, with the possible exceptions of the Alexandria Gazette and the Northern Virginia Sun and New York Times. No Internet, alas, no National Public Radio, and just three television networks to tell us the way it was.

STONE: Your family and maybe two others may have been the only practicing Jews within several blocks and perhaps the only Jews period. Any anti-Semitism there? Or brushes with it elsewhere?

ROTHMAN: Absolutely none was apparent from our neighbors—totally in keeping with the reinvention meme. Wonderful people. A few miles away at my high school, I encountered a touch of anti-Semitism, but hardly at an Adams level (“We are in the hands of the Jews”). The Belle Haven Country Club, just outside Alexandria, admits Jews today but was Christian-pure for many years. In Maryland, as late as 1948, some real estate people were not selling to Jews; and I’ve even heard that in the ‘30s or so, the Washington Star was not hiring Jewish reporters. That changed, of course, well before Carl Bernstein worked there and went on to help expose Watergate for the Post. You can read more on Jewish-related topics in Scandals as a Northern Virginia Jewish novel.

STONE: Early on, you were a bit distrustful toward the press. Oh, come on—don’t newspapers always print the truth?

ROTHMAN: Topic A at the University of North Carolina, or close to it, with sports excluded, was a ban against communists speaking on campus. I ended up talking by ham radio to Barry Goldwater, aka K7UGA. I asked him about the ban and learned he was against it—a position he confirmed in writing for my scoop in the Daily Tar Heel. That fit in well with the libertarian side of him. Well, along came a wire service report that Goldwater favored the ban. I was hardly a Goldwaterite, but with a signed letter in front of me in plain Goldwater English, who was I to believe the mainstream media? I’m just sorry I didn’t transfer my skepticism quickly enough to another matter, news coverage of the Vietnam War. Most of the newspapers in those days were cheerleaders for it, exactly as so many are today about our misadventures in Afghanistan, history be damned. Looking back, despite my fond memories of my friend the Post editor with the flattop, I take it very personally that LBJ rewarded Russ Wiggins with a UN ambassadorship.

ROTHMAN: Topic A at the University of North Carolina, or close to it, with sports excluded, was a ban against communists speaking on campus. I ended up talking by ham radio to Barry Goldwater, aka K7UGA. I asked him about the ban and learned he was against it—a position he confirmed in writing for my scoop in the Daily Tar Heel. That fit in well with the libertarian side of him. Well, along came a wire service report that Goldwater favored the ban. I was hardly a Goldwaterite, but with a signed letter in front of me in plain Goldwater English, who was I to believe the mainstream media? I’m just sorry I didn’t transfer my skepticism quickly enough to another matter, news coverage of the Vietnam War. Most of the newspapers in those days were cheerleaders for it, exactly as so many are today about our misadventures in Afghanistan, history be damned. Looking back, despite my fond memories of my friend the Post editor with the flattop, I take it very personally that LBJ rewarded Russ Wiggins with a UN ambassadorship.

One way to reform the press, of course, was to be the press, and I not only majored in journalism in Chapel Hill but also went on to some graduate work elsewhere at A Famous Journalism School. Oh, those lectures on urban affairs! I was an instant Jane Jacobs partisan, pro-neighborhood, while the professor came across to me as more of a Le Corbusier sympathizer in favor of high rises, the Pruitt-Igoe mess notwithstanding. More importantly, AFJS cared less about writing as writing and more about other matters, such as whether a story had a typo. Just one could be lethal. I retreated from AFJS, finished a first novel I’d already begun, the should-have-stayed-in-the-drawer variety; and then I worked for the Journal in Lorain, Ohio, a steel-and-automobile city on Lake Erie near Cleveland, a factory town with maybe 100,000 people at the time, tens of thousand more than today.

Trifles such as lively prose, curiosity and empathy counted more at the Journal than an ability to deprive copy editors of gainful work. And talk about an education! Lorain was exactly what I needed, a complete contrast in many ways to D.C. Red dust from the smoke stacks of U.S. Steel fell upon the southern part of town. The Journal’s offices were far more factorylike than the current variety at many papers, and in fact, you could step from the city room into the shop and smell the hot lead. Black wire service tickers clacked out the news. Just one look at your surroundings, and you knew you were working in a genuine news factory, with not that much distance between white and blue collars. The late Bill Greider, The Nation‘s national affairs correspondent, noted the same about another Ohio paper when he was writing about journalism and class differences, and he was so, so right.

Trifles such as lively prose, curiosity and empathy counted more at the Journal than an ability to deprive copy editors of gainful work. And talk about an education! Lorain was exactly what I needed, a complete contrast in many ways to D.C. Red dust from the smoke stacks of U.S. Steel fell upon the southern part of town. The Journal’s offices were far more factorylike than the current variety at many papers, and in fact, you could step from the city room into the shop and smell the hot lead. Black wire service tickers clacked out the news. Just one look at your surroundings, and you knew you were working in a genuine news factory, with not that much distance between white and blue collars. The late Bill Greider, The Nation‘s national affairs correspondent, noted the same about another Ohio paper when he was writing about journalism and class differences, and he was so, so right.

Among other stories, I covered the funeral of Bill Scroeder, the ex-Eagle Scout and ROTC cadet whom the Ohio National Guard killed at Kent State on May 4, 1970, inspiring praise from some local Nixonians. That’s history, alas, not just a few words in Scandals. In a bloody way, Richard Nixon’s crowd had bought the war home. I can also recall asking the wrong questions about Vietnam at a Billy Graham news conference and ending up in a locked room at the Oberlin police station. I haven’t any doubt that certain Ohioans would have wanted reporters shot dead at Kent. Why stop with students? Ohio wasn’t all like Mississippi, of course—far from it; dozens of nationalities lived in Lorain and still do, including many Latinos. The African-American novelist Toni Morrison came from Lorain, the setting for at least one of her works; and the town had a good library system, as a Pulitzer Prize-winning literary critic raised there can attest. Was it coincidence, both Ms. Morrison and Michael Dirda growing up in Lorain? Probably not. Lorain wasn’t Bethesda, but the schools and libraries may well have helped.

While I never met Toni Morrison, I can recall meeting such fly-in celebrities as Jane Fonda (target of sexpot jokes from the copy desk), George McGovern (a mediocre story—mea culpa) and George Wallace (a hurried but friendly interview on the tarmac at the Toledo airport) and Norman Mailer (not at all his famous feisty self—in fact, a little self-deprecating, as in his observation that writers aren’t smart enough to be doctors or good-looking enough to be actors).

While I never met Toni Morrison, I can recall meeting such fly-in celebrities as Jane Fonda (target of sexpot jokes from the copy desk), George McGovern (a mediocre story—mea culpa) and George Wallace (a hurried but friendly interview on the tarmac at the Toledo airport) and Norman Mailer (not at all his famous feisty self—in fact, a little self-deprecating, as in his observation that writers aren’t smart enough to be doctors or good-looking enough to be actors).

STONE: I’ve heard that in your Lorain days, you were the ultimate city-room terrorist.

STONE: I’ve heard that in your Lorain days, you were the ultimate city-room terrorist.

ROTHMAN: Absolutely—wilder than you in many respects, even if you protest early-morning meetings by showing up in your pajamas. A Lorain buddy named Greg Stricharchuk recalls the Rothman anecdote. Irving “Leibo” Leibowitz, the editor of the Lorain Journal, wanted me to wrap up a poverty-beat story. But the source at the other end was spilling too much. Why should a mere editor, even the much-beloved top man at our 40,000-circulation daily, interrupt my research? Ignored, Leibo summoned Bill Scrivo, the managing editor, who yelled at me to hang up. “Don’t mind that crazy person,” I told my source in my best Hildy Johnson style. “Keep talking.” He did. Leibo had always appreciated my telephone skills, but now they were coming back to bite him. A few minutes later Scrivo yanked the phone cord out of the wall.

The city editor, Frank Dobisky, still alive and a friend of mine after all these decades, was the next to demand my six or seven feet of copy paper—successfully, as Greg and I recall. Six feet? Yes. Remember this was the era of Smith Corona typewriters and paste pots (detail: the above picture does not show the exact Smith Corona model that I used, but it’s close enough—perhaps a portable version of my Journal machine).

Frank ordered me out of the city room while my piece underwent editing. “Of course,” Greg wrote on Facebook, “Rothman goes to the first floor and calls the person again. It was a Front Page day at the Journal.”

Exactly. The wild ones didn’t all vanish along with whiskey flasks from America’s newsrooms; some just went to work for small-town newspapers and, in time, Web sites—assuming they weren’t entrepreneurial or desperate enough to start their own. Let me add that I’ve been around my share of drinking people but am myself a teetotaler even on Passover. Imagine what I’d have been like with a full flask.

Reportorial stubbornness, despite the misery inflicted on poor Leibo, can also come in handy. Years later I was freelancing off-camera for ABC News in Washington, and I was 90 percent certain I had the goods on a midwestern businessman, a government landlord among other things—none other than Sam Zell, as I recall: the same man who would go on to buy the Chicago Tribune, the very paper where Greg worked. Ah, the glory ahead! I’m trying to remember who was anchor that day. Frank Reynolds? Still, temptations notwithstanding, I wanted one last call. So ignoring the ABC producers just as determinedly as I did Leibo and the others back at the Journal, I phoned the man’s office and found out that I was in what I’ll hereby dub “a ten percent situation.” My obstinacy was prudence in disguise. The ABC people weren’t reckless; but how much easier it could have seemed at the time to gamble on the odds!

STONE: What about your other adventures reporting on the General Services Administration?

STONE: What about your other adventures reporting on the General Services Administration?

ROTHMAN: Yawn. Wasn’t that the main topic of your earlier interrogation of me? But now here’s a little personal twist. GSA was my father’s old agency, the same one for which he had toiled in a converted warehouse without air conditioning. He’d started out at the General Accounting Office or elsewhere, and GSA came late in his career, well after its trajectory was set. I’ll deliberately use the passive, the “was.” At my father’s level in Washington, things just happened or maybe didn’t, perhaps stymied in his case by anti-Semitism in the lower ranks of the federal bureaucracy eons ago, as well as by his heart condition.

STONE: So considering the timing, GSA had little to do with his not being a top-dog ‘crat?

ROTHMAN: Nothing, in fact. Post heart attack—my father almost died of one in his 40s—my mother cared more about his health than his place in the D.C. hierarchy. She aggressively discouraged him from being a careerist.

Beyond that, the real villain here was a mix of socioeconomic challenges and the Great Depression. My father was the third child of immigrant parents with broken English, the very kind of Eastern European Jews against whom Henry Adams ranted in Education. Dad’s family most likely owned few books other than religious works, perhaps most in Yiddish. Simply put, in many respects, though not all, he might as well have been growing up in a ghetto-y part of Anacostia.

Dad bus-boyed his way through New York University, only to enter the job market as the Depression was starting up, so he was thwarted not just by the circumstances of his birth but also by its timing. Of course, the right luck and talent would let “Jews without money” prevail anyway. Uncle Martin, the oldest in my father’s family, won a football scholarship and ended up a dentist living in Westport, lecturing or guest lecturing at Yale, and editing the Journal of the Connecticut State Dental Association. Marty and I were close; in fact, he is how I learned about my great-grandfather the Jewish tax collector.

Now here’s the real kicker in my father’s case. While he lacked Marty’s status, he actually had some artistic abilities; and later in life he made a very minor name for himself with acrylics, collages and paintings on rice paper and was even a guest on Maury Povich’s talk show while Povich was still local. Today he just might have scored in a field like Web design. If nothing else, he might have fared well in any era as a painter-decorator, an old-fashioned craftsman, which is what my paternal grandfather was after his Navy Yard days. How unfortunate—society’s fixation on white-collar accomplishments. Correctly or not, I recall that at least one of B.F.’s sons went into some line of blue-collar work, and if he did so by choice, that strikes me as a form of sanity.

STONE: Speaking of talents and skill sets, what was a D.C. novelist doing freelancing for the National Enquirer, the ultimate blue-collar rag?

ROTHMAN: The Enquirer came to me as a result of my GSA reporting. As a writer, how could I turn down an American cultural phenomenon? No Kennedy- or flying saucer chasing for me, though. And I ungratefully rejected an assignment to interview the dwarf on Fantasy Island about his thoughts of suicide. In fact, Herve Villechaize did go on to kill himself. Gory auto accidents I could handle in my Lorain days, but I lacked the stomach for the Villechaize kind of story. Instead I wrote government waste pieces and how-tos and pop-psych articles. Scandals mentions a National Enquirer stringer ordered to use the phrase “dollops of caviar.” In reality, it showed up in a story I wrote on high-living diplomats from impoverished countries, although I don’t remember if “dollops” came from me, the editor or an interviewee.

If nothing else, the Enquirer freelance gig taught me how to write Web-catchy headlines. The whole experience was preferable to the K Street life for me, or to being a mouthpiece on the Capitol Hill. Even in the heyday of print newspapers, the respectables in the Fourth Estate were not generally throwing large sums of cash at freelancers off the tennis and dinner-party circuits. And I already knew enough about myself and the Washington dailies to realize I probably wouldn’t be comfortable as a staff writer if one of them slipped up and hired me. I admired B.F., but beyond the typo issue, it turned out that his worldview just wasn’t mine. Can you imagine me worshipping Russ Wiggins?

Still, I also see the positives of Big Journalism, which helps us monitor Big Government even if reporters and editors can be as timid as bureaucrats. Bloggers can score scoops, but most lack the skills and resources for close day-to-day coverage of Congress and the bureaucracy. We need all kinds of media. Even tabloids serve a purpose in the journalistic eco-system. Was the New York Times the first to give us the lowdown on John Edwards, the baby, and the hush money?

STONE: How could an unrepentant Roosevelt-lover like you end up writing a piece for William F. Buckley, Jr., and National Review?

ROTHMAN: Bill and I simply happened to agree on the need for an Electronic Peace Corps—people in the U.S. using computers to share technical expertise to developing countries and otherwise improve life there. No political conversion here. He knew I was incurably liberal. I’d written him out of the blue, perhaps after the Post published my EPC idea or I pushed it on National Public Radio. My logic was that if I could win WFB over, my idea would face less opposition from conservatives. The irony is that Bill was far ahead of most liberals on the issue. Turned out that Jerry Glenn, a foreign aid expert, was already doing some of the things I wanted in 1980s. Hello, Obama? Still isn’t too late for an EPC on a grand scale. And if the Republicans make trouble, just quote WFB.

STONE: You also freelanced a few pieces for The Nation, under Carey McWilliams, on phony public interest groups and other topics.

ROTHMAN: Among my other subjects was Roldo Bartimole, the I. F. Stone of Cleveland, Ohio, whom I interviewed while at the Lorain Journal. Roldo put out a little newsletter called Point of View, and was a role model for the young and uppity at the Lorain Journal. He’s still at it on the Web. And in certain ways, not much has changed. In Cleveland and so many other cities, the local governments at times care too much about certain business people and their mega projects and not enough about such boring matters as pothole fills, vital neighborhoods and good schools. Maybe in some aspects of civic life, Henry Adams could have found a kindred spirit in Roldo. “To the New England mind,” Adams writes in Education, “roads, schools, clothes, and a clean face were connected as part of the law of order or divine system. Bad roads meant bad morals.”

I also met the I. F. Stone of Washington—I’d toyed with the idea of writing a biography of him. If nothing else, I got a cafeteria lunch out of it; Stone may even have paid. Izzy counseled me to read Eminent Victorians. Hmm. Izzy as a Cardinal Manning or Florence Nightingale? I doubt he meant a comparison. But if nothing else, that was a gentle way of talking me out of the bio project while educating me, and he remains a hero of mine. Your last name is a tribute of sorts. I lacked Izzy’s focus on foreign affairs but admired his ability to defy the rest of the world.

STONE: You edited an international tech magazine, too, and a financial site and newsletter for an investment company.

ROTHMAN: I was managing editor, then editor of High Technology Export & Import, no longer published. May I add that some of my best writers were the worst proofreaders? Given my AFJS experiences, it was fun seeing my spelling theories confirmed in real life. I’m anti-typo and the rest, of course. But that is why proofers and copy editors exist; shame on newspapers for laying off so many. The mainstream media should leave typos to experts such as bloggers.

As for the financial Web site and newsletter, I helped grow the company’s managed assets from $30 million, when I started, to more than $150M at the height of the Nasdaq. I even concocted a way for clients and prospects to receive color videos of the owner’s spiels through their e-mails; and I recruited a WGMS classical announcer to pitch the company on financial stations in her dulcet voice. I was not a Registered Investment Advisor. The site and paper newsletter simply reflected the stock recommendations of the company, and I conscientiously quoted from the likes of BusinessWeek to flesh out the RIAs’ endorsements of such trusted names as WorldCom, Enron and Tyco International. Executives from all three ended up behind bars, of course; don’t you love the perspicacity of Wall Street and the press?

STONE: Yeah, the integrity, too. Now what about your e-book site and related activities?

ROTHMAN: TeleRead.org in its earlier forms goes back to 1992 when it wasn’t even an Internet domain yet—I was calling for a well-stocked national digital library system blended in with local schools and libraries, another idea that Bill Buckley liked. For hardware, I suggested multiuse color tablets with detachable keyboards, iPads more or less. Later I cofounded an organization called OpenReader.org, which had the nerve to suggest consumer-level standards for e-books. The main e-book trade group pre-empted us with its own standard, ePub, and that was fine with me despite my worries that the usual suspects would compromise the standard to fit their corporate objectives. My goal for OpenReader was to get a standard in place, as opposed to our running the e-book industry. Today the iPad and almost all other brands of e-book-capable machines can read ePub directly or through added software, and sooner or later Amazon may come around.

I envisioned TeleRead as a nonprofit, but the big foundations cared less about mere books—even the electronic variety—than about more fashionable technologies like virtue reality. So to keep TeleRead alive and open up additional time for other activities and health-related matters, I made the site more commercial and sold it to some old-media people who had founded a magazine that became TV Guide or at least part of it. The completion of a circle, almost. Remember, my origins are hardly the new media variety. I rebought the site in 2015.

STONE: So what are the lessons you’ve learned at the personal level?

ROTHMAN: A few of them are similar to Adams’, with my own variations. I like the old bigot’s better side—his generally principled approach and his respect for the past. Regardless of the publication I’ve freelanced for, be it the National Enquirer or the Nation, I’ve done so for the most part on my terms. No Kennedy- or UFO-chasing, remember. I believed in my work at the investment company, too; I myself bought some WorldCom. Adams seems to have been the same way for the most part, no small handicap in many business situations. A lesson in the education of both of us.

When I’ve succeeded, it’s often and perhaps mostly been while at odds with the usual “wisdom,” and that might apply to Adams as well. Do you realize how crazy it was to be talking up e-books for public libraries in the early 1990s? Would that I have listened to my maverick side early enough about Vietnam or WorldCom! As for Adams, some “conventional” educators must have considered him ready for the loony bin, given his theories of learning and distrust of formal education. He actually had the nerve to suggest that teachers could learn with their students rather than just pour facts into their heads. A bit Internet-like, wouldn’t you say? Imagine Adams presiding over a forum, blog or wiki on American history. I can!

Like Adams, too, I’ve been preoccupied with obsolescence, just as you are in Scandals—whether about people or the old Linotype machine in the lobby of the Telegram. Adams felt that the times were making him obsolete, that his education in the classics and his old aristocratic values were actually a barrier to success in the era of the dynamo. I myself am a proud plebe despite my family’s magnolia side, but I can still identify with Adams in many ways. Imagine all the changes that I myself have lived through—for example, the decline of the print media and even of old-fashioned American English, not to mention modern changes in values at the expense of traditional liberalism.

On the Web these days, many people use “their” to refer to individual companies and even favor “who” as a relative pronoun when writing about corporations. I don’t care if this is accepted in the U.K. and in developing countries. As grammar and as an accidentally implied worldview, what does it all say? From a traditional American linguistic perspective as well as a liberal political one, I’m grouchy. Corporations are not just collections of human beings; they are also piles of paper and swarms of electrons and vast aggregations of inanimate objects, and all too often the real estate, computers and numbers come before the people. I blame technology and globalization and old-fashioned greed and obtuseness for the tendency to confuse humans and corporate entities, especially when it comes to laws governing political donations. Adam himself might feel the same way in my place. Bad roads do suggest bad morals, in that members of the business elite are corrupting the system and keeping too much of the wealth to themselves at the expense of the commonweal.

In a related vein, I wonder how Adams would feel about our apparently being so close to the era of cyborgs, when distinctions between humans and machines will blur. How will corporations and others react? Imagine the moral and ethical issues raised, not to mention the pesky little matter of obsolescence. Adams talks about his education being obsolete, but what if the very material we’re made of can no longer cut it? Will the 30-percent humans—whatever the standard for quantifying this—prevail over the old-fashioned 100 percenters and even the 90 percenters? “We have the right stuff to build human brains,” according to Leon O. Chua, an expert in electrical engineering. Technology and biology are converging, and I feel rather reactionary compared to the young people today who are looking forward to cyborgdom.

Still, on many and perhaps most social matters, I’m not Adams, especially on ethnic issues and the need for a cosmopolitan outlook. Close to half of TeleRead’s visitors at its peak came from outside the U.S., and I would not have wanted it any other way—considering all the brilliant articles and comments that we attracted from the “company who” people” in distant places. Ethnic tolerance and economic growth actually can go together, given the greater talent pool if you keep bigots like Adams from interfering, just so you don’t let credentialism and the related values edge out commonsense. No need to recall all the Asian entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley or all the damage that America’s 9-11 xenophobia has wreaked. When I had my heart attack, a Korean-American surgeon saved me, and maybe some Jewish doctors could have helped Adams live past his 80 years. Today writers haven’t any choice but to look ahead to more of a multiethnic future. In a few decades, nonHispanic whites will be a minority among readers here in the United States. When I wrote the first draft of Scandals in the 1970s, it lacked the foreword by your great-grandniece, Rebecca Kitiona-Fenton, director of the Institute for the Study of Previrtual Media, who happens to be “Jewish-Samoan-Wasp-African-Hispanic.” Despite the satire, or maybe because of it, the Rebecca mentions just might serve as a bridge to the multiethnic readers of the late 21st century.

STONE: How much does The Solomon Scandals resemble Democracy, Adams’ novel?

ROTHMAN: Differences exist between the inner D.C. elite and the outer fringes, and Scandals reflects the latter worldview. Despite Adams’ protests at times that he was not insidery enough, he never forgot that his grandfather and great-grandfather had been President. I don’t know of even one President Rothman. Adams’ family history certainly influenced his perspective in writing Democracy and added to the appeal of his works among a certain class. I’m reminded of an old quote from George Gissing, the Victorian novelist, in New Grub Street: “Men won’t succeed in literature that they may get into society, but will get into society that they may succeed in literature.” Adams was already there, born with a brand name.

Now, the similarities between Democracy and Scandals—despite the latter’s more informal style and use of the first-person voice. Both are Washington political novels set during fictitious administrations. While Scandals is a suspense novel and a newspaper and political novel, it is also a novel of manners, and that is what some critics might consider Democracy to be most of all. The plots of both novels include secret cash transactions and other white-collar crimes in the best Washington tradition. Both raise the question of, “How much can we reform the political system, and if change isn’t possible, will you compromise yourself by being part of it or even associating with those who run it?” Adams’ protagonist, Madeline Lee, will be going off to Egypt, while your destination is Hollywood. Neither town, L.A. or D.C., is angelic. You just want a change.

STONE: But you’ve given away your ending! You’ll be drummed out of the suspense novelists’ union.

ROTHMAN: Not at all, Stone. I still haven’t spilled all the twists in the Afterword. His antisemitism and other bigotry aside, Adams might have liked how Scandals winds down.

Slightly Updated August 19, 2023

Discover more from The Solomon Scandals

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.